Remember Lot's Wife

How do objects help us to remember? And in what ways do they also, paradoxically, facilitate forgetting? This post reflects on this pair of interconnected questions by exploring the significance of an intriguing eighteenth-century earthenware dish.[1]

Now part of the Glaisher Collection in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the item was produced by the Staffordshire potter Samuel Malkin (1668–1741). Although dated 1726, it may have been made several years later. This is not a unique object: at least two other similar dishes associated with Malkin’s factory survive, suggesting that the design was expected to attract buyers and that it became a commercially viable line.

Adorned with the phrase ‘Remember Lot’s Life’, the dish alludes to St Luke’s Gospel 17:32. A striking example of what Juliet Fleming has described as ‘speaking crockery’, it is an object that draws attention to its status as a mnemonic.[2] Like the wide range of other pieces of Protestant pottery that survive in public and private collections, this example of domestic tableware is self-consciously didactic. It is intended to operate as a tool for prompting rumination and remembrance within the sphere of the home.[3] The imperative tone of its inscription presents memory as a moral obligation. While many such plates were intended for display on sideboards or dressers rather than for use in serving food, it would be a mistake to see this as a merely ‘decorative’ object. Resisting any polarity between aesthetic and function, it is indicative of a culture in which eating and drinking were saturated with religious meaning and in which meals were a moral affair. It is also an emblem of the ‘social universe’ created by the dissemination of the vernacular bible in post-Reformation England.[4]

Drawing on the patterns provided by illustrated bibles, episodes such as this were frequently deployed as themes for the interior decoration of godly households.[5]

The story of Lot’s wife was a less popular subject than the Old Testament favourites like the Temptation of Adam and Eve, Abraham and the Sacrifice of Isaac, and Susannah and the Elders. The passage from Luke inscribed within the rectangular frame is a record of the words Christ spoke to his disciples in anticipation of his death and resurrection. He reminds them of the divine judgement that befell the iniquitous cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, the citizens of which ate, drank and engaged in fleshy and wanton pleasures until they were destroyed by fire and brimstone raining down from heaven. ‘Even thus’, he tells them, ‘shall it be when the Son of man is revealed’. When the day of the Second Coming arrives, their duty is to forget the past and embrace the glorious future represented by the return of the Messiah.

Luke 17:32 is itself a remembrancer of Genesis 19:26. The verse in question is the culmination of the tale of the escape of Lot and his family from annihilation. Instructed by two angels, he leads his sons and daughters to safety before Sodom is consumed by flames. However, his wife lingers behind and disobeys the injunction not to look back. Her punishment is to be transformed into a pillar of salt, an enduring monument to posterity of the mortal dangers of pride, infidelity and apostasy. The physical act of glancing behind her is a figure of the foolish pity she feels for the city that was her home. It betrays her secret longing for a corrupt way of life that has provoked the anger of God. It is a form of remembering that draws down his wrath. Her crime is nostalgia for a world that is on the cusp of being lost.

To remember Lot’s wife is thus to remember an event precipitated by a failure to forget. Early modern preachers often invoked her petrification as a warning of the perils of backsliding to popery and idolatry. They used it to reprove the lukewarm piety of a populace overly attached to earthly comforts and as an incentive to sincere and earnest repentance. Fossilised in the very moment of her transgression, she documented the Lord’s righteous intolerance of ungodliness. Her metamorphosis turned her into a memorial of the spiritual death that awaited all sinners, in short into a memento mori. The stylised structure upon which the verse from Luke’s Gospel is incised is akin to a funeral monument or a monumental title page. The two trumpeting angels flanking Lot’s wife give the object sonic dimensions, as if sounding the alarm to the Last Judgement.

The legendary fate of Lot’s wife was also widely understood as an indictment of wifely insubordination. Her anonymity in the biblical record signals another form of punishment: the suppression of her personal name functions as a form of damnatio memoriae. It is itself a sentence of oblivion. The gendered dimensions of the message carried by Malkin’s plate should be underlined. Often acquired or given on the occasion of a marriage, visual objects such as these also served to underline the responsibilities of women within patriarchal households, not least their duty to show deference towards the rule of their husbands. Like the stories of Eve’s seduction by the serpent and Susannah’s false incrimination by the Jewish Elders, they also operated as stern reminders of the virtue of chastity and the evils of lust. Viewers of this dish would have also been prompted to recall the sequel to our Genesis episode. Lot and his daughters retreat to a cave, where the latter, worried that the family line will be extinguished, ply their father with drink and then sleep with him in order to preserve his seed. Both are begotten with children in an act of incest that resonates in the background of the image on this earthenware dish. The scene was frequently depicted in contemporary woodcuts, engravings and paintings. A mid-seventeenth-century print by Wenceslas Hollar shows the inebriated Lot sitting on the lap of one daughter, while another stands over him with a jug of wine or ale.

The lonely figure of his late wife stands in silhouette in the distance.[6] In its extended form the story links drinking with debauchery and culinary with sexual temptation in a manner that sent a clear message about the need for sobriety in contexts of consumption. This piece of pottery invites the spectator to look forwards as well as backwards, to the future as well as the past that God apprehends in an eternal present that transcends the constraints of human time. As well as being a mnemonic object, it is thus also prophetic.

Malkin’s earthenware plate offers insight into how objects help us to both remember and forget in other ways too. It illustrates Andrew Jones’ point that regarding material things merely as containers for storage and as systems of signs impoverishes our understanding of the part they play in the creation and mediation of memory. Memory is forged by the embodied engagement between human beings and these objects, by habitual movements and repetitive gestures that inscribe it in the mind. Their materiality is integral to how people encounter and reconstitute the past. It is the sensory experiences of seeing and touching, hearing, tasting and smelling, that brings memory into being.[7]

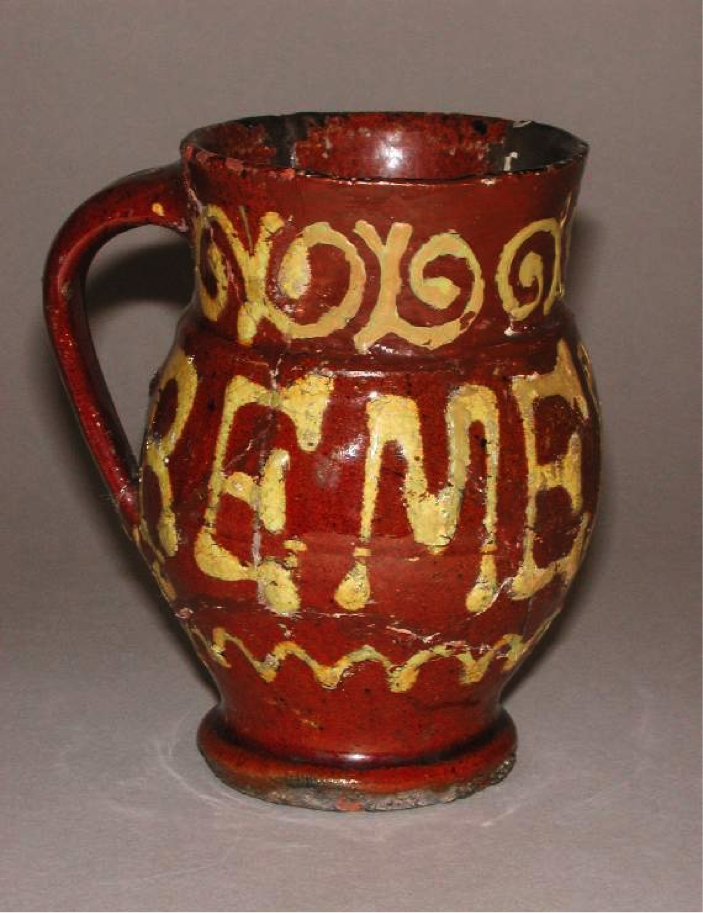

Like this seventeenth-century mug that carries the slipware inscription ‘REMEMBER GOD’,[8] this artefact produces memory in the current of quotidian and mundane activities. But it also fashions agency of another kind. Ironically, it makes its viewers and users reproduce the very crime committed by Lot’s wife herself: it compels them to look back, to return to a moment and place when and where sin reigned. It requires them to remember what this unnamed woman was urged to forget. And it fosters an equivalent form of pious forgetting through the mechanism of remembering, demonstrating the uncanny, slippery process whereby some things are best forgotten only after they are remembered.

We know little about the provenance of the remarkable lead-glazed earthenware plate that has been the subject of this post. Once part of the collection assembled by the renowned French porcelain artist Marc-Louis Emmanuel Solon during his time working in the Minton factory in Staffordshire, it was sold in 1912 to a buyer acting for Dr James Glaisher, the fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, whose consuming passion for early ceramics seems to have rather eclipsed his interest in mathematics. Glaisher bequeathed his collection to the Fitzwilliam Museum on his death in 1928. By contrast, we can trace the movements of another virtually identical specimen now owned by the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. This dish apparently travelled across the Atlantic with the English Quaker immigrants Joseph and Martha Townsend. They settled in East Bradford Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where they attended the Birmingham Friends Meeting. The plate passed down to their daughter Hannah Townsend, who married Nathan Sharpless in 1741, as an heirloom.[9] In the process, it acquired a fresh layer of memory. It came to function as a double remembrancer. In intertwined the recollection of a biblical story with profound spiritual resonance with the recollection of past generations of the Townsend family. Perhaps it even prompted them to look back to the old World which they had left in search of a new Jerusalem. Perhaps it too served to stimulate nostalgia for what they had lost.

[1] Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, C.201-1928. http://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/72995.

[2] Juliet Fleming, Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England (Philadelphia, 2001), pp. 145–58.

[3] Andrew Morrall, ‘Protestant Pots: Morality and Social Ritual in the Early Modern Home’, Journal of Design History, 15, no. 4 (2002), pp. 263–73.

[4] Naomi Tadmor, The Social Universe of the English Bible: Scripture, Society and Culture in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2010).

[5] Tara Hamling, Decorating the ‘Godly’ Household: Religious Art in Post‐Reformation Britain (New Haven and London, 2011). Examples of the scene of Lot and his family escaping from Sodom and Gomorrah include Gerard de Jode’s print in Thesaurus sacrarum historiarum ceteris testament (1585): British Museum, 1968, 1018.1.30.

[6] Wenceslaus Hollar, Lot and his Daughters (1652–1677): British Museum, 1867, 1012.487.

[7] Andrew Jones, Memory and Material Culture (Cambridge, 2009), esp. ch. 1.

[8] Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, GL.C.37–1928. http://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/77058.

[9] Winterthur Museum, Delaware, 2010.0004.001 (http://museumcollection.winterthur.org/single-record.php?resultsperpage=20&view=catalog&srchtype=advanced&hasImage=&ObjObjectName=&CreOrigin=&Earliest=&Latest=&CreCreatorLocal_tab=&materialsearch=&ObjObjectID=&ObjCategory=&DesMaterial_tab=&DesTechnique_tab=&AccCreditLineLocal=&CreMarkSignature=&recid=2010.0004.001&srchfld=&srchtxt=Malkin&id=bcbe&rownum=1&version=100&src=results-imagelink-only#.XUWW4y-ZPHg). See also Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa M. Minardi, Paint, Pattern, and People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725–1850 (Delaware, 2011), pp. 16–20; The Luther Effect: Protestantism – 500 Years in the World (Deutsche Historisches Museum, 2017), p. 189.