(Un)binding the Cantiones Sacrae: the York Minster part-books

Remembering the Reformation is, of course, by necessity an ongoing act of reconstitution. I take the central questions of my own brief, ‘Events and Temporalities’, to be these: what temporalities emerge in the process of that reconstitution, in our encounters with our objects of study? And what can the proliferation of religious understandings of time and history in early modernity teach us about our own methods for approaching those objects? What follows is a brief narrative of one encounter with one object that challenges any easy assumptions we might make about the fixity of two related sets of boundaries: temporal ones, and confessional ones.

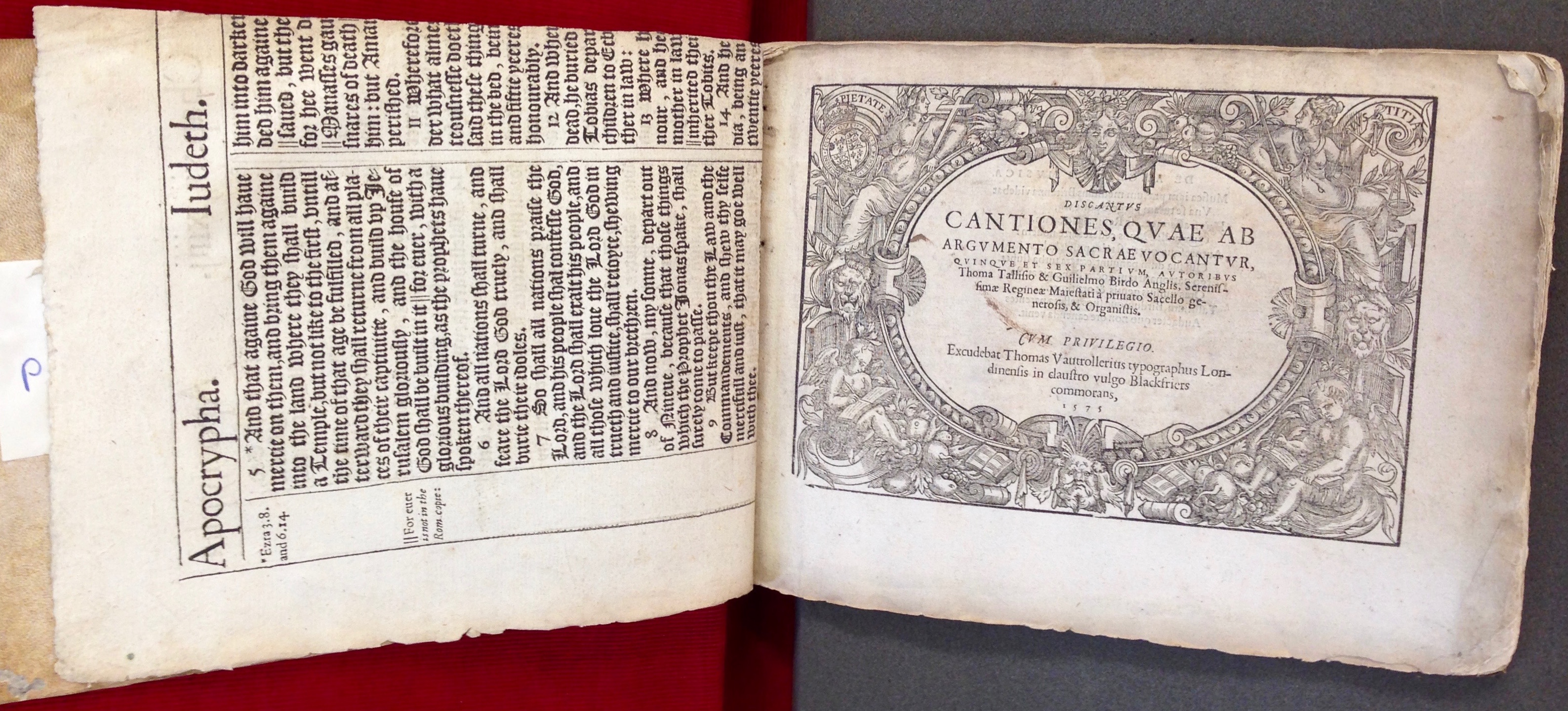

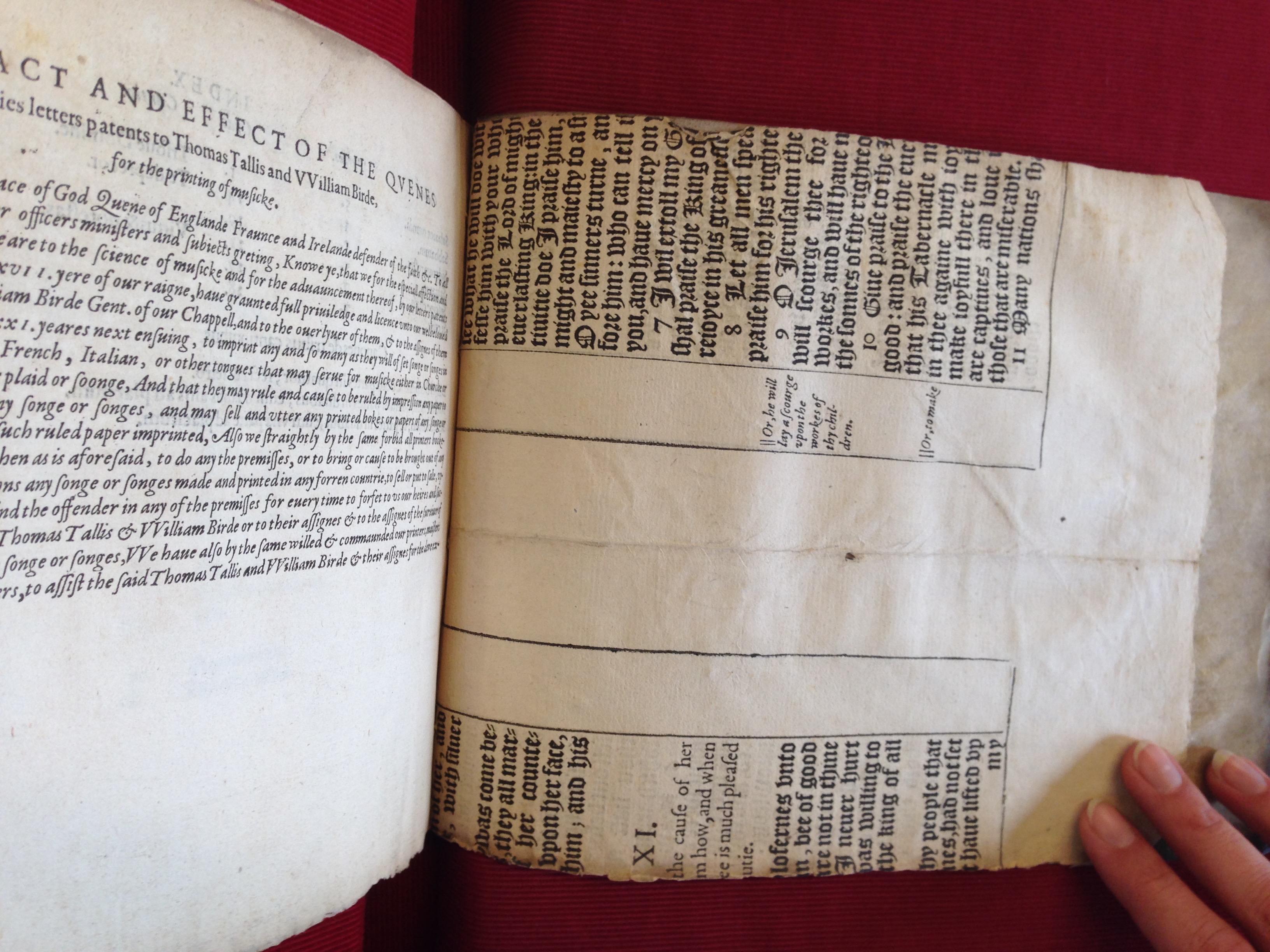

In 1575, the composers William Byrd and Thomas Tallis, known recusants, gentlemen of the Queen’s Chapel Royal, and possessors of the sole privilege to print music in England, published a volume of polyphonic vocal music casually known as the Cantiones Sacrae. Its full Latin title is one of my favourite acts of Reformation rhetoric: Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur — ‘songs which, according to their subject, are called sacred’. The equivocation neatly sidesteps the question of which music is rightly called ‘sacred’, while at the same time pre-empting any potential accusation of popery. Published as six vocal parts in oblong octavo, each part has its own title page, bears a dedication to Elizabeth at the front, and incudes at the back a précis of Byrd and Tallis’s privilege, promising the visitation of the Queen’s ‘high displeasure’ upon any other man who should undertake to publish music. Literally enfolded in royal authority, these ambiguously sacred songs both strenuously proclaim their political legitimacy and decline to worry overmuch about their confessional identity.

If we consider the Cantiones in the abstract, and thus locate it in 1575, an artefact of its original moment, the story more or less ends there. But the copy in the York Minster Library tells a more complex story. The Minster’s five part-books, lacking the sixth, are bound in vellum, and on the front cover of each volume is inscribed in an early hand the composers’ names and the relevant vocal part, as well as the title translated into an English that evacuates the Latin’s delicious ambivalence: ‘Tallis and Birds sacred songs of 5.&6. partes’. But what interests me most about these volumes is what stands between their vellum bindings and the printed music:

Each of the part-books is bound with a fragment of a sheet from an English bible, four of them leaves from a KJV of 1611, 1613, or 1617 (STC 2216, 2224, or 2247) the fifth from a different 1613 folio edition (STC 2226). Three of the fragments come from the same sheet, the outside of quire 4O — the end of Tobit, and passages from Judith. They make a good joke: ‘Apocrypha’ announced in large type, opposite songs that hedge on the validity of their own sacredness. I wonder whether whoever stitched these sheets together anticipated by four hundred years my involuntary (and mildly embarrassing) bark of laughter in the reading room.

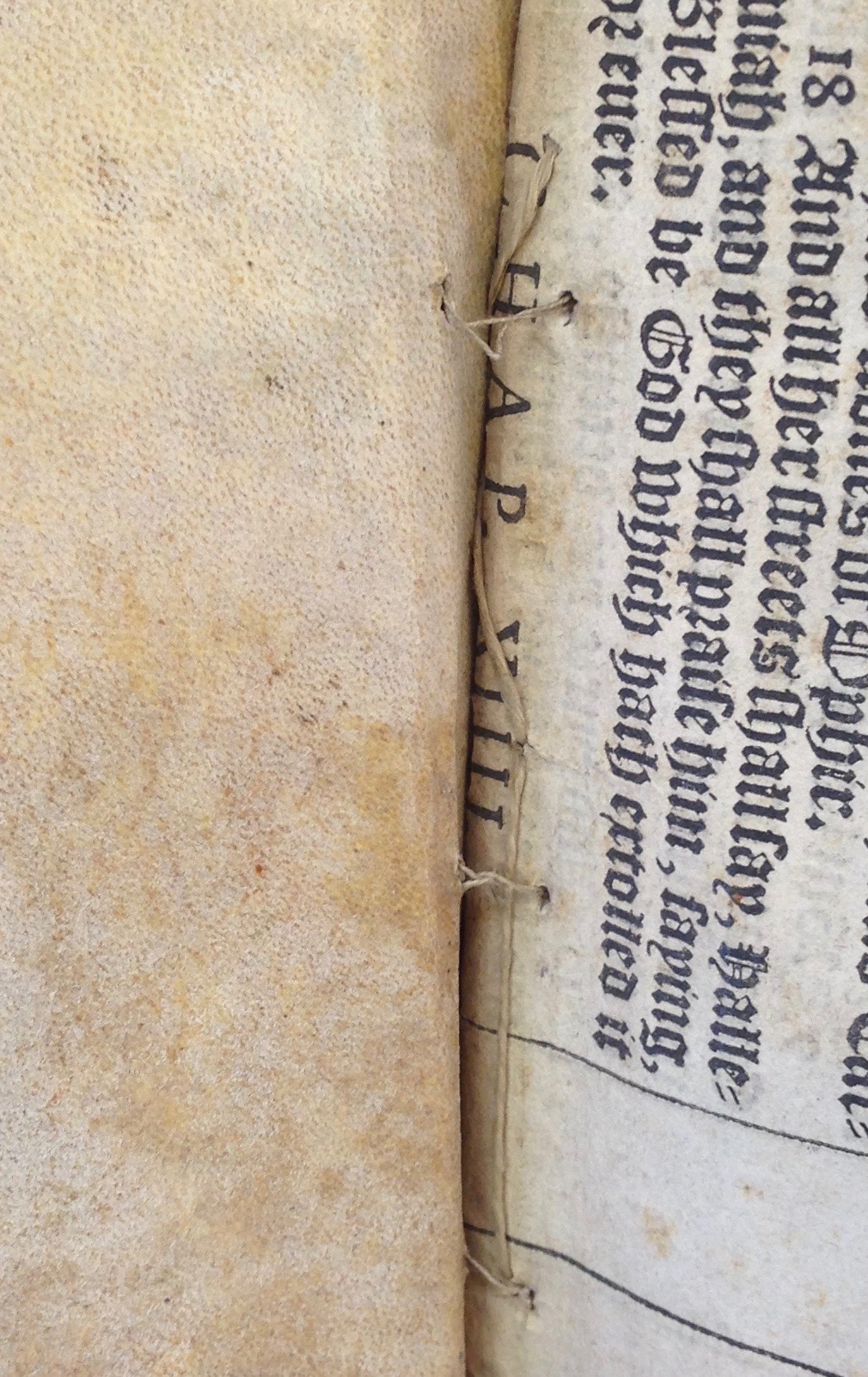

The fragments also give us some clues about their life before they were waste:

The crease down the centre of the sheet, the stab hole in the crease: these sheets were stitched, if not bound. They were a Bible before they were waste paper. Two distinct sets of stitches let us know that the waste paper binding preceded the vellum one:

Questions proliferate. Which edition and impression of the KJV is this, and why was it dismantled? A book on the scale of these huge folios was too costly to destroy casually, so why would, say, a bookseller do it? A good book historian, keen-sighted, might be able to identify the exact impression on the basis of these small fragments; such work might reveal that these sheets come from an impression that had to be recalled due to error. When, where, and by whom was this work done? Certainly between 1611 and the time of the vellum bindings, which on the basis of the hand on their covers mustn’t have been more than a couple of decades later. Stitching inelegant but sufficient to withstand four hundred years, as well as apparent ready availability of printed waste paper suggest that a book professional (printer? seller?) cut and stitched the waste sheets, but again this question requires a book historian.

I am not one, but I know a folio sheet from a handsaw, so I reconstructed this one — first by hand and then digitally, using composite images from EEBO. My mechanical work in the reading room reversed the procedure performed by the person who bound these leaves: mentally unstitching the waste scraps, pasting them back into a sheet, imagining the sheet as the outer page of a quire bound in a complete Bible. Doing this little exercise brought me into a kind of intimate contact with the temporal phenomena these books generate.

Each of the five parts of the Minster’s copy of the Cantiones comes from at least three times. Its printed pages, its waste paper binding, and its vellum binding each represent one of three disparate moments, materially stitched together. It is, in other words, an anachronism. The temporal identity of these books is of cultural and religious consequence: the Cantiones mean something different after 1611 than they did in 1575. They pose little doctrinal controversy at the date of their publication — just enough to provoke the syntactic ironies of their title — but by the time of the publication of the KJV, Tallis had long since died and Byrd had begun to publish openly controversial music, most notably in his masterwork the Gradualia, a vast experiment with the Catholic liturgy, printed in 1605, then hastily withdrawn in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot, and then cautiously republished in 1610.

Their temporal perversity, in other words, enhances our understanding of their confessional perversity. But it’s worth saying that there’s nothing especially scandalous about the kind of book this is, or the kind of anachronism it is. The enveloping of suspiciously Catholic music in fragments of a destroyed King James Bible is an outrage only if we take for granted a set of overdetermined confessional boundaries assigned to Elizabethan and Jacobean England by later study. Situating this book appropriately in confessional terms requires, ironically, loosening the boundaries between confessional positions. By a similar turn of irony, situating it appropriately in time requires developing a tolerance for anachronism.